Without arts and culture, you don’t have a society

Interview with Rabih El-Khoury, Metropolis Cinema

The Metropolis Cinema Association is dedicated to promoting independent cinema in Lebanon and the MENA region through a diverse program of film screenings, industry training, audience engagement, film education and film preservation. Working in tandem, Metropolis Cinema and the Cinematheque Beirut bring together film enthusiasts from across different fields in an environment conducive to the creation and study of cinema. Metropolis Cinema chose to present Erased,__ Ascent of the Invisible as part of the Cinema of Commoning Film Program.

For this interview we spoke to Rabih El-Khoury, who has been with the cinema in various roles since its foundation in 2006, about this organization’s remarkable evolution.

A Cinéconcert takes place at Metropolis, February 2019 © Metropolis Cinema

A Cinéconcert takes place at Metropolis, February 2019 © Metropolis Cinema

Introduce us to Metropolis – how would you describe the type of work that you do as a cinema? What is special about your cinema space?

Rabih El-Khoury: Metropolis opened its doors in 2006, as the only arthouse cinema in Beirut, Lebanon. I joined the team in March 2006, shortly before its inception. Our director, Hania Mroue, had the wish to fill a void in a landscape dominated by multiplexes showcasing mainstream Hollywood blockbusters. There was already a niche audience familiar with arthouse films in the country due to existing festivals like the European Film Festival and Ayam Beirut Al Cinema’iya [Beirut Arab Cinema Days]. At that time, we had no idea if there would be an audience to come every night to watch films, but we forged ahead despite this uncertainty. We began in a modest 110-seat basement theater in central Beirut.

We opened on 10 July 2006 with a rerun of the Semaine de la Critique program from the Cannes Film Festival. We had a fantastic opening night, then the next day war broke out, The July War. During the war, Metropolis evolved into more than just a cinema and it became a refuge for displaced children. Hania did a fantastic job at the time, leaving everything that we were supposed to be doing when a new cinema opens and a festival is running, to take care of the kids. After the end of the war, we managed to relaunch the cinema, but this was a slow process because we were still trying things out.

When you open a new cinema sometimes you have role models in mind. “I want to be like this or that cinema” or “No, I want to be something like a multiplex.” In Lebanon, we didn’t have these reference points. With no established model to emulate, every decision was trial and error. We had to imagine how things could be. How do we deal with the projectionist? What do we do if we have a problem with the 35mm projector? Who can fix it for us? We didn’t have a budget because nobody wanted to fund something like this. However, we kept going and we felt we were doing something innovative. We were starting to get people interested and we were doing a bit of advertisement and promotion here and there. We wanted to have a program that ran continuously. So despite the slow start, this place was starting to take shape and we were starting to imagine things.

We were a very small team. I started as an administrator, but I also did the ticketing and sometimes I would clean the cinema. You don’t care what task you do, you just want to be part of it. Suddenly people started coming to the place, and international organizations also began to be interested in working with us. We started with an ARTE Film Week in collaboration with the European cultural channel, we did a special week with Les Cahiers du Cinéma. By 2008, our location felt too small. The public kept coming, and festivals wanted us to host them. So we decided to move to a larger venue. We rented a theater with two screening rooms which was part of a functioning multiplex. This expansion allowed us to diversify our programming. We have hosted acclaimed retrospectives of Jacques Tati, Luchino Visconti, Michelangelo Antonioni and Alain Resnais, to name a few, and have established our own animation film festival, Beirut Animated, which sheds light on animation practices in the Arab World. We also became the home for festivals such as Ayam Beirut Al Cinema’iya [Beirut Arab Cinema Days]. We have hosted many film premieres and established a young audience program. Despite setbacks, including the forced closure in 2021, when the owner of the building forced us to shut down, we persisted.

What gave us energy to keep going is that we could see that people were eager to follow what we were doing. Sometimes we would have people come and say, “I hated that film tonight, but I’m definitely coming tomorrow.” This makes you feel that people are ready to accept your choices and be part of it. We had some glorious years at the cinema. And although the country has been through a complete meltdown, Hania’s vision continues to guide us. We aim to inaugurate a new space for Metropolis Cinema this summer, depending on the political situation in Beirut. This would become the first space that would be just for us, without being dependent on renting a space from another entity.

The Launch of the Cinematheque Beirut in 2018 © Metropolis Cinema

The Launch of the Cinematheque Beirut in 2018 © Metropolis Cinema

You mentioned that there have been some difficult political moments in Beirut, and throughout the years there have been so many political crises in Beirut, yet you have managed to persevere. What is your role in this political landscape?

I’m going to give you a real example to answer this. During ARTE Film Week in 2012, we opened with Leos Carax’s Holy Motors. It was fantastic, it was sold out. On the second day, there was an explosion that killed a very important security officer in the country. This explosion happened 50 meters away from the cinema. I was in my car, we were going to a restaurant to have lunch, and I passed the site of the explosion but because I had my windows closed and I couldn’t hear any sounds from outside. Suddenly I see all the cars opening their doors in the middle of the street, like you’re in a movie, and I’m thinking “What the hell is going on?” So I look behind me and there is this huge cloud of smoke coming from the direction of the cinema. When I finally managed to reach Hania, she told me that there had been a huge explosion in the neighborhood.

When I finally made it to the cinema, the guy at the ticketing desk asked me “Are we opening tonight or not?” At that moment, I decided that this is our strategy: If we have two people buying tickets, we will open the cinema. If no one shows up, we will close. At 7:50pm, we had two people waiting who had bought tickets. And I remember the usher saying, “Rabih, what is wrong with these people? Somebody has just been killed and we are opening the cinema.” And I said, “Look, we have been through so much, that people just want to see something different. They want to escape this reality, they want to disconnect a tiny bit for one hour.” By 8pm, we had 40 people lining up to buy tickets. So we screened the film.

The next day, we had programmed Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives. We had a 35mm print, we were so excited about it. This was the day when the officer who had been assassinated was being buried, so Beirut was a total mess, but about 70 people came to see the film. A lady whom I will never forget, came to me after the screening and said “I’m not sure I got anything out of that, but I’m absolutely thrilled to have been on a journey which made me dream and see things differently and experience such a weird film. I enjoyed whatever I could from that.” After that, we became aware that all the cinemas in the country had closed, apart from ours. We were the only cinema still welcoming people. This really makes you really think. On one hand, we went through the July war, we went through a mini crisis in the country, the government has been toppled. We had explosions. On the other hand, we were always facing budget questions. It’s an arthouse cinema, it’s a cultural space, nobody wants to fund that. You have to get foreign funding, work with embassies, which is not always the ideal thing, but you have to make it work. Hania was really a mastermind in always managing to find money for the place.

Going through all of that, we always had this urge to be there, to continue, to do things for the people, to make sure that the public is coming, to make sure that even in times of tragedy people would get to experience something a bit different. We were aware that no matter what you do in Lebanon, you always have setbacks. Political issues, economic crisis, whatever. But you have to deal with it, you get used to it, and you fight back. This was our driving force. We have always been a small team of people who were really eager to keep going, and that really pushed us forward. Of course, it was very difficult, no question. The Ministry of Culture has the smallest budget of all the Ministries in Lebanon. So it has not been easy, but you channel it and turn it into something more positive. We always found solutions and made compromises so that we could continue doing things.

An outdoor screening takes place © Metropolis Cinema

An outdoor screening takes place © Metropolis Cinema

The Metropolis Cinema Association also runs the Cinematheque Beirut, which aims to conserve Lebanese and Arab cinema heritage. Why is this kind of archival work so important to you? What role does archive play in the present?

Cinematheque Beirut was initiated later as part of the Metropolis Association. Metropolis cinema is the physical space, while the Metropolis Association is the entity behind it. Currently, we are in the process of building a physical space. Cinematheque Beirut emerged out of necessity, because of a lack of archival material. Many Lebanese and Arab films from previous decades either don’t exist anymore, have disappeared, or are in poor condition. We wanted to create a platform to reconnect with our past by finding and preserving archival material. This includes posters, articles and documents. Metropolis has always showcased contemporary and classic films, but we realized we weren’t screening our own classics. Lebanon and the Arab World have produced cinematic masterpieces, yet they were hard to access. Why is it so difficult to screen these films? Why does the new generation not know about these films? Why can’t we find Egyptian or Moroccan prints? So we initiated the Cinematheque Beirut not only to preserve Lebanese cinema but also to explore Arab cinematic heritage. Each country must safeguard its cinematic legacy, and for us, that task lies with the Cinematheque Beirut.

Why are we always thrilled when we have classics in our programs? And why are we always thrilled when we have a classic, to be able to say “this is the restored version?” We’re very thrilled when we screen a Jean-Luc Godard or Yasujirō Ozu film in our space, for example. Last year I saw Tokyo Story at Arsenal and I cried in the cinema. Why can’t we see our own classics? Why can’t we have our own classics restored? Why do we have to fight to finance the restoration of films that are part of our heritage? Sometimes it feels like our governments want to erase periods of time completely. For instance, with the Lebanese Civil War, nobody wants to talk about it. We know everything about the First and Second World Wars, but we know nothing about our own war. I didn’t learn anything about it when I was in school. When governments try to eliminate complete eras from our history, everything within those eras disappears too. Films don’t exist, materials don’t exist, and even buildings demolished by the war are replaced with something new and posh.

What Metropolis wants to do with Cinematheque Beirut is to try to remember. Enabling us to search for, dig up, and showcase our archive is a way to reconnect with our collective memory. We have no chance to study, learn, or understand what happened in our past, but at least we can discover what people did. This is why it’s very important for me to have archival material that offers not a journalistic but an artistic perspective on the Lebanese Civil War, reflecting on our past and its consequences so we learn not to repeat the same mistakes. We can help newer generations understand what happened before. Metropolis’ work is very private and personal. Of course, there are also like-minded institutions working on collective memory in various ways. Sometimes we collaborate, sometimes it’s very individual. We all strive to connect with our past in order to understand our present and future. For me, this is the importance of being in touch with the archives—to understand our past.

Young audiences gather at Metropolis Cinema © Metropolis Cinema

Young audiences gather at Metropolis Cinema © Metropolis Cinema

Since we are discussing the past so much, we also wanted to ask about the future. What is the state of film culture and film education in Lebanon right now? Do you feel there is hope for filmmakers in Lebanon, despite the difficult political situation?

Arts and culture might no longer be a priority in the country. However, without them, you don’t have a society, in my opinion. It is very important to allow children to explore their artistic side—to push them to learn a musical instrument, see films, put on plays, sing, whatever. In Lebanon, this has never been a priority, so it was really a personal endeavor, to bring the kids to the cinema so they could see something different.

This period is very difficult for the country. It’s not just because Lebanon has been in meltdown mode since 2019, but also because the area we live in is very complex. What’s happening in Gaza is heartbreaking, and I don’t want to imply that screening films is more important than education. I just wish that people would get in touch with arts and culture because it helps you grow, see the world differently, and understand that artistic freedom is also a freedom of expression. That’s why I believe it is very important to encourage the newer generation to get in touch with the arts.

When we made our program for young audiences at Metropolis, millions of kids came. We made sure that kids from the camps could come see films free of charge. We organized buses for them so that they could come watch films together. Of course, many people are leaving the country, but some people don’t have that chance. And I don’t want everyone to leave. Each person has the freedom to choose what they want to do with their lives. That’s why we are building the new space for Metropolis—to give people the chance to come together, see films, and perhaps think about the country’s future. Even though this period is very difficult, it will not last forever. We have always experienced ups and downs in Lebanon, and hopefully, the country will be okay again. If it is, Metropolis will be there, accompanying the new generation, not just to see films but to screen their own films with us.

You chose Ghassan Halwani’s film Erased,___Ascent of the Invisible to screen as part of the Cinema of Commoning collaborative film program. The film explores how we deal with archives in an absence of images. How does that question about archive and absence relate to the work you do at Metropolis?

This film deals with the disappeared individuals from the Lebanese Civil War who have never been found. It also deals with the disappearance of archives. We know nothing about these people; it’s not only the people who are missing but also the information about them. When we think about cinema, we often deal with things that we know existed but are no longer there. We had press posters, 35mm reels, and more, which are now gone. We asked ourselves, how can we address an archive when an archive does not exist? How do we make a film about that? Ghassan Halwani beautifully addressed this in his film. Ghassan also has a personal story, as he lost someone dear to him who was never found. One aim of Cinematheque Beirut is to try and answer questions like, “Where are these things? Where are these people? Why can’t we find them?” In a program like Cinema of Commoning, we wanted to present a film that deals with archives that are absent or simply don’t exist.

Ghassan uses archival material and animation to explore the stories of the thousands of people who disappeared during and after the Lebanese Civil War. Interestingly, his film has resonated beyond Lebanon, and has had a tremendous tour in Latin and South America, where many have experienced similar tragedies. This film speaks to universal themes of loss and the search for understanding, making it relevant in many contexts, such as Ukraine and Gaza, where people are also disappearing. Cinema can bring us together, even in our tragedies, to share common experiences.

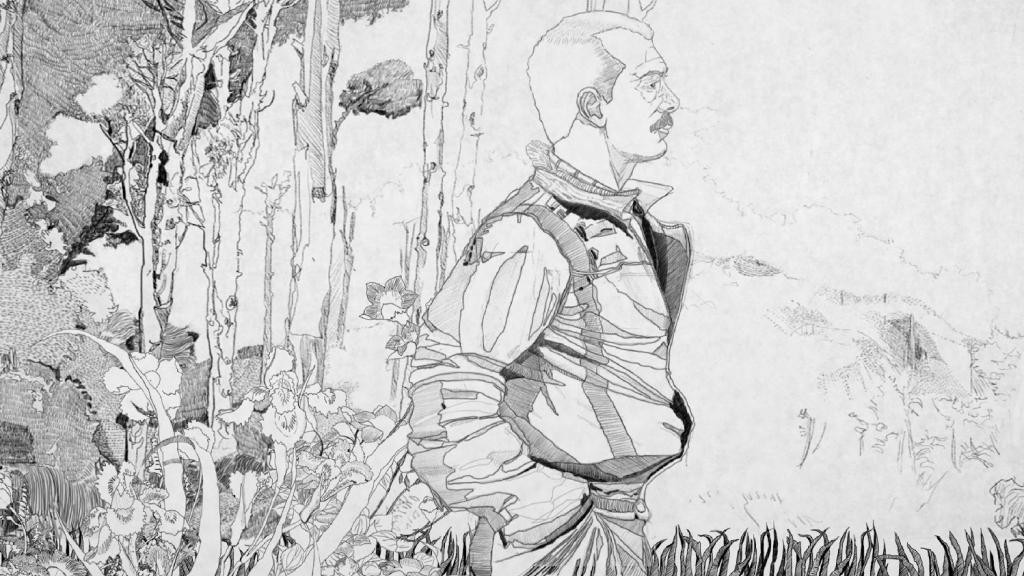

Erased,__ Ascent of the Invisible, Ghassan Halwani

Erased,__ Ascent of the Invisible, Ghassan Halwani

How do you collaborate with other cinemas and archives dedicated to promoting and preserving Arab cinema’s past and present? How does solidarity with like-minded initiatives in the MENA region help your mission, particularly during difficult times?

Metropolis was a founding member of NAAS (Network of Arab Alternative Screens), now based in Berlin. The network was created in Beirut, but some years ago, it moved to Berlin because the situation in Lebanon was extremely difficult, especially with finances, money was just evaporating. This network has grown over the years, starting with like-minded institutions in the Arab world reflecting on common problems. Budget issues, for instance, are a common difficulty. How do we fundraise for independent spaces? How do we support each other with finding solutions, ensuring the circulation of Arab cinema, and dealing with subtitles due to different dialects?

The network is expanding, it now includes institutions from Morocco to Sudan and Iraq, creating a vast network. It’s challenging to meet everyone’s needs, but at least there’s a space for conversation and imagining possibilities. Institutions in difficult regions, like Yemen and Sudan, benefit from this support to exist, survive, and screen programs. Establishing and growing this network is important for supporting these institutions.

What do you feel is the role of cinemas in building community and safe spaces, especially in contexts affected by war, terrorism, and political adversity?

Every space wants to have an audience, and it’s important to always be in conversation with that audience. I remember when we started with a retrospective of Antonioni’s films. Someone asked: “Can you do Fellini next?” So we made it happen with the help of the Italian Institute. The audience member who had made that request came to me and said, “ Wow, I can’t believe that you listened to my comment and you made Fellini happen.”

We were there every night at the cinema, presenting films, welcoming people, and listening to them. I was also there every night. Sometimes kids would come and say, we would like to see James Bond. And I would explain that we weren’t showing James Bond, because you could see that somewhere else if you want to, but here we are offering the chance to see something different. I remember once a kid said, “Oh my god, this film My Neighbor Totoro is so sweet!” It’s great to be in touch with your audience, especially a younger audience. Some people were really thrilled to come back to the cinema to experience films together as a community of young cinephiles. Seeing this response enables you to think that you’re not just opening the cinema for yourself, you’re screening films for an audience.

As a curator, I have often presented films that were not my cup of tea, because I thought they made sense for the public. For me, you’re in conversation with the audience the whole time. And because of this, you suddenly start understanding your audience and what the audience needs.

When we did this ARTE Film Week, I remember there was one year when I told Hania that the films I had chosen were very difficult, but that I was sure that audiences would come because they had seen programs with us before. That edition was phenomenal. I thought there would be 25 people each night, but to have 100 people there in a single night, for films coming from Serbia, Portugal or Brazil it really meant that the public was eager to discover different stories, a different cinema. For me, this was really a gift that came from us doing things together with the audience. It’s a give and take. Some years later, this concept of collaborative programming with guest curators kickstarted with our conversations with the audience.

A full screening at Metropolis Cinema © Metropolis Cinema

A full screening at Metropolis Cinema © Metropolis Cinema

What does a Cinema of Commoning mean to you?

For Metropolis, being part of a program like Cinema of Commoning means being in touch with like-minded institutions, especially from the Global South. We don’t have chances like that. As programmers, curators, filmmakers and artists, working in cinema you get to meet individuals, but it’s different to be able to be in a program that brings together institutions. We talked about NAAS, which is a very specific network for Arab arthouse institutions, but what Cinema of Commoning is proposing is different, as we don’t often have the chance to work with institutions that are based in Africa, or Southeast Asia or elsewhere. These institutions deal with similar issues, like lack of funding, government support, censorship, access to material. Thinking together with these institutions helps us learn from each other and collaborate creatively. How can we learn from each other? How can we collaborate together? And also, how can we let our institutions grow?

Cinema of Commoning provides a platform for people to come together, especially since institutions in the Global South do not have the chance to mingle or be on a panel together. But to have this experience, this almost year-long program that concludes in a symposium, is also something that I, myself, but also as a representative of Metropolis as an institution, could benefit a lot from. Metropolis, established in 2006, and continues to be a learning experience for us. If I can learn from you, I will be thrilled.

Is there anything else you’d like us to know about Metropolis?

I hope initiatives across the Global South receive more encouragement and governmental support. It’s not about flourishing; it’s about bringing communities together to screen and discuss films. This environment may enable one or two persons to decide, “I want to be a filmmaker in the future” or, “I love sound, can I work as a sound designer in Lebanon.” There are people from the industry who can say, “the first film I saw was at Metropolis”. That is so thrilling for me, to hear that you watched something in our cinema and you decided to become a director or a producer or an actor. Of course, we’re in the digital age, where people stream films online, but nothing beats the cinema experience for me. You can have the best equipment at home, but there’s still such value in coming to see a film in the cinema, in laughing and crying with the others, in screaming at the cinema owner afterwards because the film was shitty. But you will come and visit that cinema again because every time you see a different film, and that’s always thrilling.

Rabih El-Khoury holds a Bachelor of Arts in Journalism from the Lebanese American University in Beirut and a Masters of Arts in Creative and Cultural Entrepreneurship from Goldsmiths, University of London. He has been working with the Metropolis Association, which manages Metropolis Cinema, the only art house cinema in Lebanon, since its inception in 2006. Initially an administrator, he became Managing Director and is now a member of its administrative board. He also worked for the cultural association Beirut DC, promoting Arab Cinema as general coordinator for its Arab film festival, The Beirut Cinema Days, from 2006 to 2015. He organized over 20 Arab film weeks in the Arab World and Europe. El-Khoury served as Program Manager of Talents Beirut between 2014 and 2019, curated the Film Prize of the Robert Bosch Stiftung from 2017 until the end of the program in 2021, and held the position of Diversity Manager at DFF – Deutsches Filminstitut & Filmmuseum in Frankfurt am Main between 2019 and 2023. He currently curates the SAFAR Film Festival of the Arab British Center in the UK, Arab Cinema Week for Cinema Akil in Dubai, is a programmer at ALFILM, the Arab Film Festival of Berlin, and collaborates with AFRIKAMERA in Berlin.