It should feel like you are entering your home

Interview with Leyli Gafarova, Salaam Cinema

Salaam Cinema is a community-based cinema and arts temple run by a team of artists and creatives. By occupying the former Molokan temple, Salaam aims to create social awareness, reclaim urban space for free cultural expression, and build bridges between different communities. It also offers a cultural program with a focus on the region.

Salaam Cinema chose to present a selection of Short Films from the Caucasus as part of the Cinema of Commoning Film Program. Ahead of the screening on Thursday 18 April at SİNEMA TRANSTOPIA, we spoke to Leyli Gararova from the team about occupying a building, Azerbaijani cinema and how to make a “non-institutional institution” feel like home.

Introduce us to Salaam Cinema – how would you describe the cinema to someone who has never visited? What is special about your cinema?

Salaam Cinema is a community-based cinema and arts space concentrating on many different disciplines nowadays, but it started mainly as a cinema project. It’s located in a historic building. If you were to come to Baku, you would see a big contrast between the space and the rest of the city, because the city has been subjected to a lot of gentrification, and a lot of historical buildings have been demolished. Even where renovations have happened to historical buildings, it is done in such a way that you don’t feel the history. Most of the time, when you walk around Baku, it’s difficult to tell if a building is old or new. It feels like a lot of retouching has happened to the city but not with heart or honesty.

When you enter our building, you experience this contrast because of the design. It looks old and handmade, but it also has a sense of anarchy and freedom. People like that. What we have heard a lot is that, when people enter our building, they either enter a parallel universe, or it makes them feel like home. This was also the intuitive approach from the beginning, when we started building this non-institutional institute: that it should feel like you are entering a house, your home, your cultural home. We wanted you to feel free to create, to write on the walls, to do whatever… This is part of what makes it unique.

Salaam Cinema occupies the site of a former Molokan temple. Can you talk a little about the history of location and the cinema’s relationship to it? How does this unique location, and the heritage associated with it, resonate with the work you do there now as artists and curators?

There have been certain events outside the building itself that have shaped our perception of what Salaam is. Back in 2016, when we started, we didn’t have a building, we were doing urban interventions. The idea was to step in where there were old cinemas which were not functioning anymore. There was a cinema called Homeland, which is something you could do a different separate thesis or PhD on, because there were cinemas all over the Soviet Union, in lots of Soviet cities, which were called Homeland in the local language. This building was also very historic; it was a caravanserai [inn] before the Soviets came, then the Soviets made a cinema out of it. After independence, the building was neglected, and occupied as a form of teahouse, and men would gather there to drink tea. So it was kind of a community intervention in itself, but only for certain groups. We started bringing old projectors, a sound system, films which we would translate, so we could discuss in the teahouse. This concept came from lots of different ideas. First of all, we had no place to go and watch films. Secondly, we were not interested in sitting in a corporate building watching Hollywood blockbusters. Thirdly, we also had this urge to watch films collectively as a social practice, and to use it as a form of open space to discuss issues.

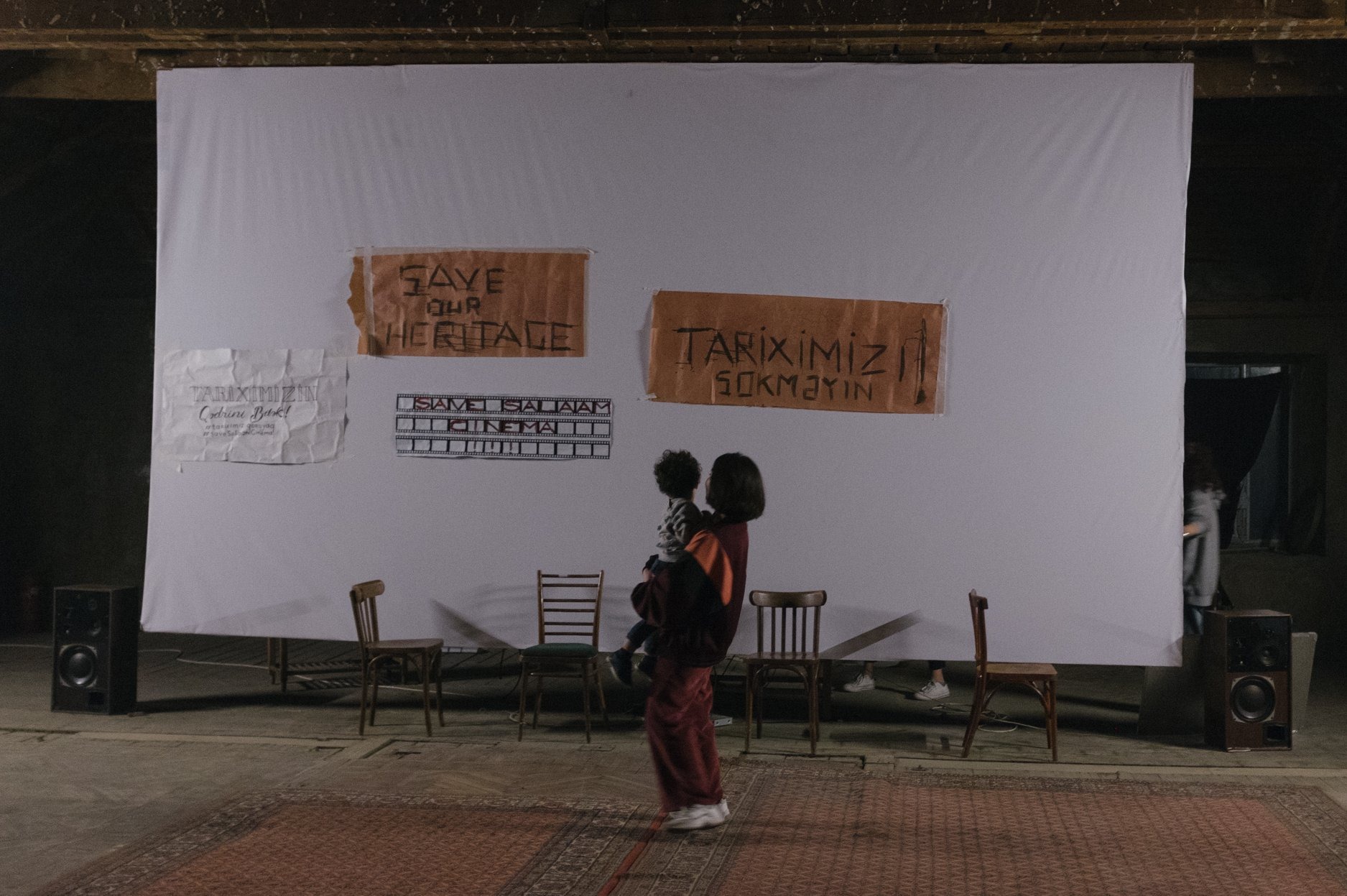

Then, one night the building was demolished. It was such a traumatic experience, in line with so many different losses we’ve endured in the city throughout the years, but it kind of determined the fate of Salaam. In 2019, we felt the need for a new space for ourselves, where we could feel like home. We always felt we needed it to be an old building. When we found this building, there were also plans for demolition. It was built in 1913, as a Molokan prayer house. Molokans are a Russian ethnic group that were also a bit anarchic in their way, because they did not accept the Orthodox Church, so they were exiled to a lot of places, especially in the Caucasus. That’s how they ended up in Azerbaijan. One of their people, who was pretty rich, decided to build this prayer house, so that they could gather there, so the building already had community symbolism. I’m not spiritual, but I do feel that the building has this spirituality. When we entered, it started to become a community space organically, without us even planning it or understanding what it was going to be. There is a certain magic about the architectural intention of the building in general.

Throughout its history the building has gone through several transformations, including being converted into a radio station during the Bolshevik revolution. It aired cultural programs and, during the independence fight in the 1990s, it was the only source of news about the Soviet atrocities which were happening at that moment. So the building is a symbol of resilience and history. After independence, many buildings in post-Soviet spaces became privatized. In the case of Azerbaijan, and many different places, they wait to be demolished to make space for skyscrapers or a residential building, which would bring the owners money. The same fate was planned for this building.Given this context, it was a bit naive and romantic of us to think that if we could enter the building that we would be able to save it from demolition. But I think, after that first experience we had, the need to do something about it only grew stronger.

In 2019, just by coincidence, we managed to rent the building for a cheap price from men who were supposed to not let anyone in.These men wanted to earn a bit of extra cash, and they had no idea what our plans were, they were just like “don’t make too much noise!” We renovated it and started organizing events. The moment we started the renovation, a lot of people began to come. Mostly people we had never met, I don’t know where they came from, we didn’t make posters, we didn’t have lots of followers, it was just word of mouth. People started to come with paint and brushes, who wanted to contribute somehow. This is how the space became part of the practice of commoning. In February 2019, we opened our doors to the public, and there was an overwhelming response. We didn’t have enough money, we didn’t have speakers. It was cheaper to buy a secondhand piano than to buy a music system, so we bought a piano and chose to show silent films. These old Azerbaijani silent films were super interesting to watch, but our curation was based on creative solutions to the conditions we were in.

It got so much attention that the owner clearly understood that this was not going to go well for him, so he decided to speed up the process of demolition. When we were out of the city for Novruz [a traditional Azerbaijani holiday to mark spring equinox], two rooms on the first floor were demolished. That’s how the drama started. They planned to demolish the interior, to make it look unsafe, which would give them the right to demolish it. We realized we had to work faster, and we started the campaign to save the building, which took several months. We were sleeping in the building.

After a couple of months, we were able to gain historical status for the building, which is unusual. Five years have passed since then, and we are still occupying the building completely. Although we have done a lot of renovations ourselves, there’s still much that needs to be done to improve the condition of the building. It’s certainly not luxurious! It’s very cold in the winter, it’s very hot in the summer, but it’s all worth it. We also have this understanding of artists as cultural workers, and of how institutions or non-institutions should be maintained. We think a lot about service and programming and how these things relate to each other. Many people have said to us “You should bring someone in who is a cleaner,” but for us that’s the point. We do the programming and we clean the toilets at the same time, and that’s a really interesting situation to think about.

Can you give us an example of an event which you held recently which brought different communities together? Or a memorable moment where you felt that what you’re doing at Salaam is all worth it?

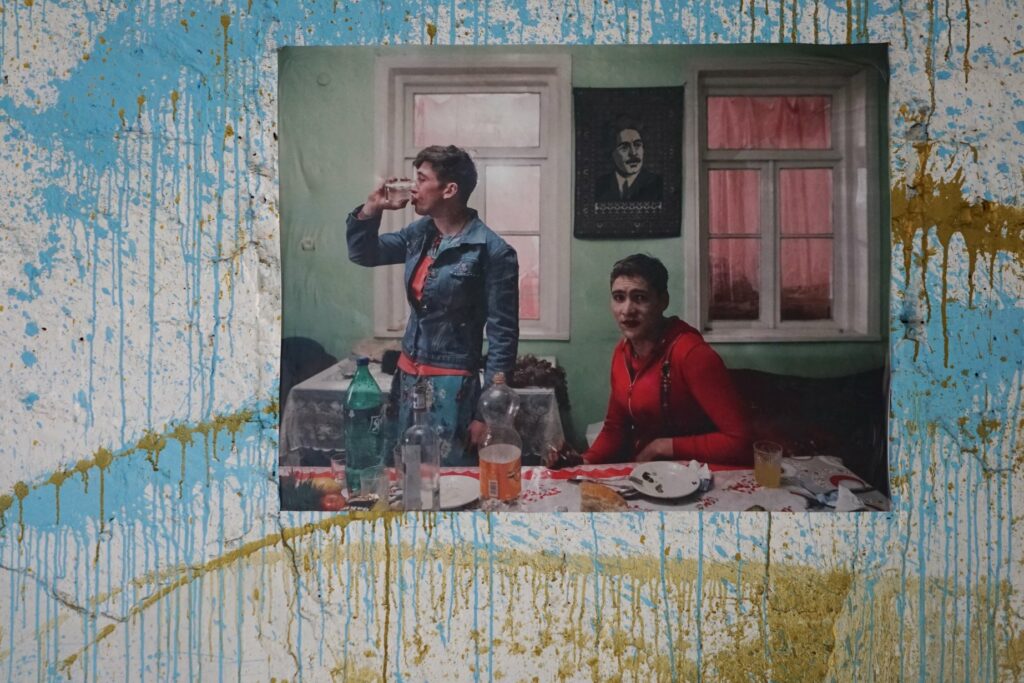

As I mentioned earlier, we began primarily as a cinema, but we’ve evolved into something more than. It was unique when we started to pull out these silent films and bring them to younger audiences who had never been able to see them before. What is very interesting about those films in general is that they carry historical weight, especially those produced in the early Soviet era..They were part of this Soviet Socialist propaganda, but also feminist propaganda. If you watch these films there’s lots to think about, such as the context of how the religious clerks are being depicted, and how the Soviets come and liberate women with education. On one hand, you see that those problems that were there 100 years ago, they’re still continuing actually, with or without the Soviet Union’s feminist policies. On the other hand, they are also a product of colonial times, part of colonial propaganda, so it’s interesting to watch them in the context of the confusing period we are living through now. We were the first ones to pull this archive out of the boxes and bring it to new audiences.

We also translate everything to Azerbaijani language, which is not something that is being done in the country, not even amongst cinemas here, because it’s too much effort for them. They either screen films in Russian or in Turkish, which also shows the relationship that we’re in between colonial powers. Our language is not being further developed in the cultural sphere. We see that also in the practice of cultural work, we’re missing a lot of specialist terminology. We do a lot of translation work into Azerbaijani.

We are also committed to the representation of queer and female artists and filmmakers. Our programming naturally includes a lot of films made by women and queer people, but that’s not due to a quota system, it just aligns with who we are. What also happened is that when our focus got dispersed over different kinds of disciplines and programming, other people started to programme the films, which I also liked a lot.The space became a shared space where other people also organize collective film screenings. It’s not centralized. People need to apply to the calendar and the work should be in alignment with our values, not sexist, or racist or fascist, but otherwise the programme is shared with others.

That’s the film part, but we now have lots of different disciplines. We have a theatrical laboratory, in which we practice dancing, performance arts, theater arts. We have a music and sound laboratory, where we experiment with music and sound. We have a sewing laboratory, a wood workshop, artists’ studios… We do exhibitions, lots of interdisciplinary experimental practice. We also decided not to focus on results but on process. So it felt interesting to invite people to the process and to understand that even if we didn’t know what we were doing, it’s all fine.

After five years, we started to feel like we wanted some tangible outcomes alongside our process-oriented approach. It’s very interesting to think about that, navigating the complexities of cultural industry traditions while staying true to our vision. Some periods, you’re very critical about something and then you allow yourself to live it, and you change from the inside and listen to yourself. Sometimes you read about process-based work, or experiential processes and it doesn’t tell you about the hardships or human processes you have to go through.

Salaam aims to serve as a safe space for isolated individuals – how do you do this practically, taking into account the political context of Azerbaijan today? What can we do as cinema workers to make our space welcoming and safe?

We’ve made it very clear that this is an inclusive space and we practice radical inclusivity. It’s a hub for experimentation where everyone can be together. The inclusivity ends when safety is under question. We do different kinds of events, and we are also located near the central station, and as in many cities this area around the station is a bit edgy. We have a huge garden, so when we are having our outdoor events, people hear us. We don’t have face control, we don’t have special questionnaires… we welcome everyone in. We have specifically chosen this approach; when your community feels empowered, it works to allow people who are not from our immediate circle to be part of it. This is a political act for us, to not segregate or isolate ourselves, but instead to use this space and cultural practice as a bridge to bring people together. It may sound clichéd, but it is true! It is what we believe our function is as cultural workers, as artists, not to segregate ourselves or even to fall into the traps of identity politics, but to bring people together and to show this utopian idea that we can all coexist. Whether it’s a music event or a concert or classical laboratory, the constant question we are working on is: “How can we live together? How can we all coexist?”

In Azerbaijan, as you must have heard, the political sphere is not celebrated for its democratic practices. To be honest, nowhere is, but we have specific challenges to face. Although there are different types of people who are part of the civil society and identify themselves with political movements, we are often not so well connected. Outside of queer and feminist groups, often other movements still have patriarchal elements. So it’s very difficult for us to identify ourselves with a certain political sector or movement. Nevertheless, I think what we do is intrinsically political, and our approach reflects this.

In your opinion, what is special or distinctive about cinema from Azerbaijan / the South Caucasus region? What do you wish international audiences knew / better understood about your region’s cinema?

I believe in Azerbaijan we are very confused about our identity as a country, and this is reflected in our film language. More films are starting to be produced, and independent cinema in particular is starting to grow. We inherited the industry from the Soviet times, where there were a lot of productions being made under state control, leaving little room for independent work. This is part of our history. On one hand, the 1990s was a time of independence, but it was also overshadowed by war. All these factors influenced cinema dynamics.

Right now, we’re starting to have more queer and female filmmakers, more independent work. This is partly a result of cameras being more accessible. One thing that I am slightly afraid of though, and would like to analyze in the future, is how are we operating in the international arena? Some of the interactions that we have raise questions about what the still dominant Western film industry wants to see and how our filmmakers respond to these expectations.

This is not just a problem in Azerbaijan, it’s a problem across the Global South. The Western film industry wants to see films which portray a conservative society, women fighting for their rights within hardships, etc. Yes, those stories are there but there are so many different stories. We also have an urban landscape, we have women working and divorcing… I feel that the industry often wants to see our rural exotic landscapes. There is this neocolonial dynamic, and we start to fall into that trap of wanting to give that to them. This is not only in Azerbaijan, I see that everywhere in the relationship between the Global South and the West. There is a certain form of exoticism. I sense that also through filmmakers who participate in labs where their projects are being developed under the supervision of, most of the time, white men. It is something which I think we need to be very careful of and develop a critique towards, too. To understand how the Soviet regime influenced our production and aesthetics, and now how the Western film industry is also influencing our aesthetics.

What does a Cinema of Commoning mean to you?

As I mentioned, I’m not particularly spiritual, but in a way, commoning is a spiritual action for me. I remember the first time when we started screening at Salaam Cinema, when the sound began on the screen and the lights went off and the people started looking at the screen… There is some magic happening there. I think Cinema of Commoning, or cultural practice as commoning (because I find it hard to separate the two) should have a spiritual aspect to it; a repetitive discipline, with room for flexibility, because then so much becomes possible.

When I got to know Cinema of Commoning, and when I read the text, it felt like someone had perfectly articulated what we’ve been doing. I’m happy to be part of this network. I would also love to discuss how filmmaking can be part of this kind of alternative practice. It would be great if we could develop further together, not just in watching films, but also in the process of creation.

Leyli Gafarova is an independent filmmaker, researcher, educator, and co-creator of Salaam Cinema, a community-based cinema and art space. Based in Baku, she focuses on processes, research, and discoveries, through the lens of themes such as gender, national identity, (self)-censorship, and co-existence. Leyli employs participatory approaches and games to experiment with authorship and collectivity, while also reflecting on and questioning production processes. Additionally, she curates film programs, educational labs, and festivals to examine and deepen the understanding of suppressed voices, identities, and narratives.