Cinemas are fuelled by people

Interview with Butheina Kazim, Cinema Akil

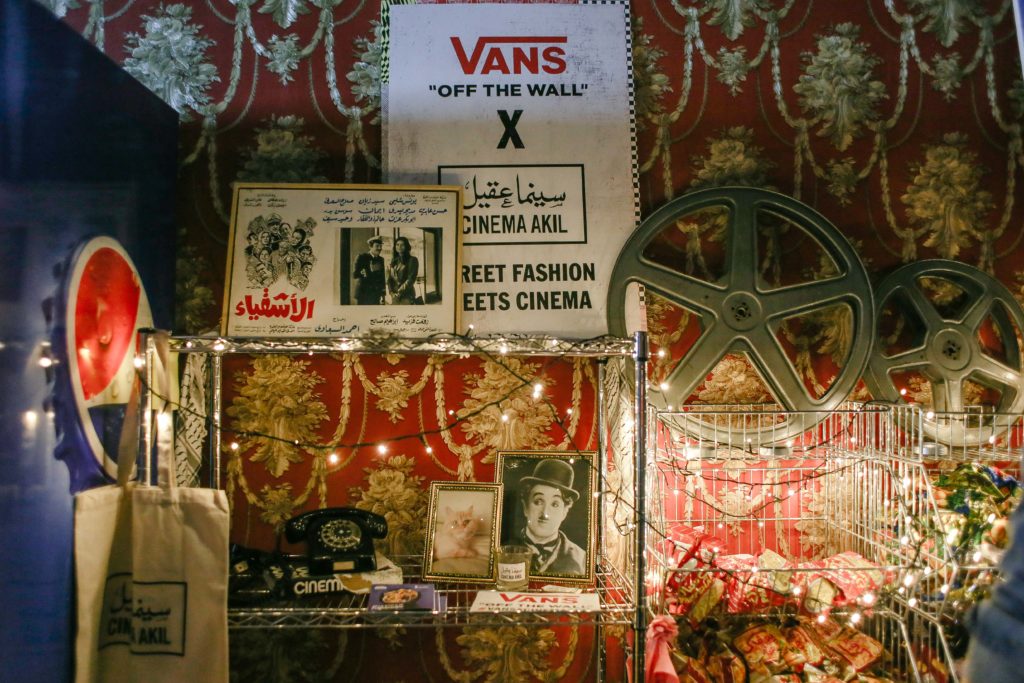

(Credit: Cinema Akil)

(Credit: Cinema Akil)

Could you elaborate on Cinema Akil’s mission and how has it changed over time?

Cinema Akil began in 2014 as an experimental pop-up with the aim of screening the kind of programming that we felt was missing from the landscape here. We wanted to know how people would engage with cinema and what those conversations might look like. To take theory into practice, we partnered up with a couple of community spaces. The first one was a gallery in a warehouse who took a chance on us. We did a six-week programme that was a smorgasbord of the different kinds of films we were hoping to show if we had a permanent venue in the future. The long game was always to have a bricks and mortar 365-days-a-year arthouse cinema space. In order to test out that idea, we wanted to take it slow and we also didn’t have the financial means to do it yet. In parallel with these gallery screenings, we also started running pop-up cinemas in order to build the audience base.

By 2017, we had done about 50 pop-ups. Through one of our frequent partners, we got an opportunity to take over a warehouse space and set up a temporary cinema for three and half months. This longer residency allowed us to ask questions about how a permanent space might function. What are all the things that this space might need? What is practical and what is idealistic? How do we make it something that belongs to the community here? We wanted to challenge assumptions and biases about what an arthouse space could look like in the region.

We worked with artist friends on designing the space, and we had all these restrictions on what we could do – for instance, you couldn’t nail a single nail into the wall. We were not allowed for licensing reasons to sell tickets, so we would sell passes. You might, for instance, have to buy a cookie to get in, and that would be the price of your cinema ticket. It was very rogue, and all driven by the energy of wanting to create this new kind of space.

The success of the first few months confirmed that there was a thirst for this kind of home for film outside of existing state structures. The barrier of entry for us was very high, as the majority of the cultural organisations in the region are predominantly state-funded. We discovered that people do not come to us for English language films, but for documentaries, regional films, shorts and experimental films. We also discovered that people came to us because of the way the space was designed. We did not have stadium seating like a traditional cinema, and people liked the idea of being altogether in this giant living room style set up.

We used these findings as a reference point to build on, scratched our initial designs and budgets, and reworked based on what we had learned from that first period. There was something about this grassroots approach and the way it was built into the building itself that people responded to, and we wanted to incorporate that into our permanent space. We were able to self-fund the project, which was a real victory, because we never wanted to be dependent on a corporate partner or the state. We were able to take over that exact same warehouse space and turn it into our permanent outpost. That became our full-time space, and our mission remains the same. We focus on what the films tell us, championing those that have been sidelined and showcasing work that expands our cinematic imagination.

How has that transition from a travelling pop-up space to a permanent outpost impacted on your audience? Have you managed to take people with you along the way or have you developed a new kind of audience as you’ve become more settled?

We did both, because the one thing that has also changed as we’ve moved from being a pop-up space to having a permanent location is that we’ve become a ticketed space. The pop-ups were free entry, and there was always a fear that if we translated this to a paid model, our audiences would dwindle. Would people actually pay for it? That temporary “Beta” cinema, allowed us to test this theory about whether people would be willing to pay for this, and whether they would return beyond the novelty of the opening season. We did manage this, partly because of the pop-ups, which had played a big role in building our community and creating visibility. People began to associate our name with this kind of programming, and they did follow us, which was great.

Dubai is a very transient place, so that’s one continuing challenge for us. We build relationships with people and then they’re gone in two years. But what also did change, especially during COVID, was that you started to see a lot more of that local audience being created. People started to see cinema as an extension of their existence, despite the temporary nature of their connection with the place. 90% of our population is expatriate, only 10% are natives from the country. We’ve managed to keep a relationship with many people, even with some who have left, which is a beautiful thing. Sometimes on a hard day, when we’re wondering why we’re just looking at spreadsheets all day to run an arthouse cinema, we will receive an email from someone who used to live in Dubai saying that the cinema was special to them; it was where they had their first date or it was a place that changed their relationship to the city. That kind of feedback restores our belief in the role that we play as a permanent space where you can always come back. People do not come to Cinema Akil, for the most part, because there’s a specific film they want to watch. They’ll come in because they want to see something at Cinema Akil, and they trust us.

(Credit: Farel Bisotto)

(Credit: Farel Bisotto)

Can you talk a little more about the principles behind your programming, especially as you’re only a one screen cinema and have limited capacity in a lot of ways. How do you curate your programme?

Cinema Akil, like all arthouse cinemas, is a respite for the underdog, a discursive and interventionist space. Where you have a dearth of places for congregation, of places where there is room for political and social discourse, then cinemas become a big player in presenting different ideas. A big programming focus for us is challenging realpolitik, through the kind of films that we show, through the ideas and stories that these films make visible. Such films make visible experiences closer to the lived realities of our audiences rather than being Hollywood renditions of people’s lives in this region. A big part of what we do is to try and counter that dominant media showing work by filmmakers from the region, real stories.

For example, we are co-presenters of Reel Palestine, a festival which embodies our principles. Our way of doing political work is through such gestures, as we are not able to explicitly have that political conversation. We let the films do the work. Many members of the founding team of Cinema Akil are women, and we are very invested in showcasing stories by women, working with female directors or highlighting female-led stories.

I have many amazing memories from our events, but one that always stays with me was this one screening that we did in Sharjah, at Mirage City Cinema. That space was conceptualised by Thai director Apichatpong Weerasethakul as part of the Sharjah Biennale. We did a shared programme with them of interregional sci-fi in conversation with cult sci-fi, as part of which we screened a film called Khatee’at Malak, followed by a screening of 2001 A Space Odyssey. The cinema has a beautiful outdoor space surrounded by residential buildings in an old part of Sharjah, and it’s not closed off. There were some kids from the neighbourhood who were passing through the space, a group of twenty boys between the ages of five and twelve. They were walking though, eating their snacks, and they looked up at the screen, just as the intro scene of 2001 with all the apes was playing. The boys were just blown away, they started shouting at the screen. Then, they sat down and watched the rest of the film. That’s exactly the kind of magic that we were hoping for, that’s what cinema can do.

Have you collaborated with other Cinema Initiatives or platforms that operate across this one region? And why is it important to you to build transnational cinema platforms for dialogue and exchange?

We are a member of the Network of Arab Alternative Screens (NAAS), a consortium of cinemas from different contexts; festivals, travelling cinemas and permanent outposts. We’ve been very committed to this since the beginning, because we really believe in making the kind of films we want to screen more accessible. This kind of process takes time, so we have been working on this collectively, discussing our shared principles. I don’t think that there’s a utopian model by which all these organisations can work together. I think it’s important to maintain independence in every context, because we are all led by our communities. Nevertheless, there are many opportunities to collaborate, through shared programming and dialogue, or by pooling resources. Such collaborations allow us to participate in programmes that span the wider landscape and challenge borders, physical and otherwise, enabling films to travel across the region.

Cinema of Commoning is a great example of what we aspire to do. There is a larger solidarity that exists, not only in terms of creating radical programming, but also in terms of shared political principles and of challenging post-colonial structures. Not every cinema shares the same views, but there is a commonality in the way we are all betting on this alternative mode of film exhibition, challenging traditional commercial models of distribution and of financing. We also try to challenge our own biases, considering collective care and consciousness, and supporting different practitioners in different contexts. These spaces are fueled by people, not by dispensable labour, they’re made up of people who have a collective investment in the principle of commoning. All of us have that shared DNA, regardless of our differences.

Butheina Kazim is the founder of Cinema Akil, the only independent arthouse cinema in the Gulf region programming repertory cinema programmes at their flagship home in Alserkal Avenue in Dubai and through the nomadic cinema across the UAE. Kazim is a member of the Steering Committee of the Network of Arab Alternative Screens where Cinema Akil is a member. Kazim lives and works in Dubai. Instagram @butheinahk | Twitter @butheina