Smashed Burgers, Flat Hierarchies, Big Dreams

A Report from Cinema Makers 2024

Cinema consultant Duncan Carson dreams of opening an independent cinema in Waltham Forest in North-East London. At the Strasbourg Cinema Makers conference he encountered a range of eye opening ideas from venues who are approaching film exhibition differently.

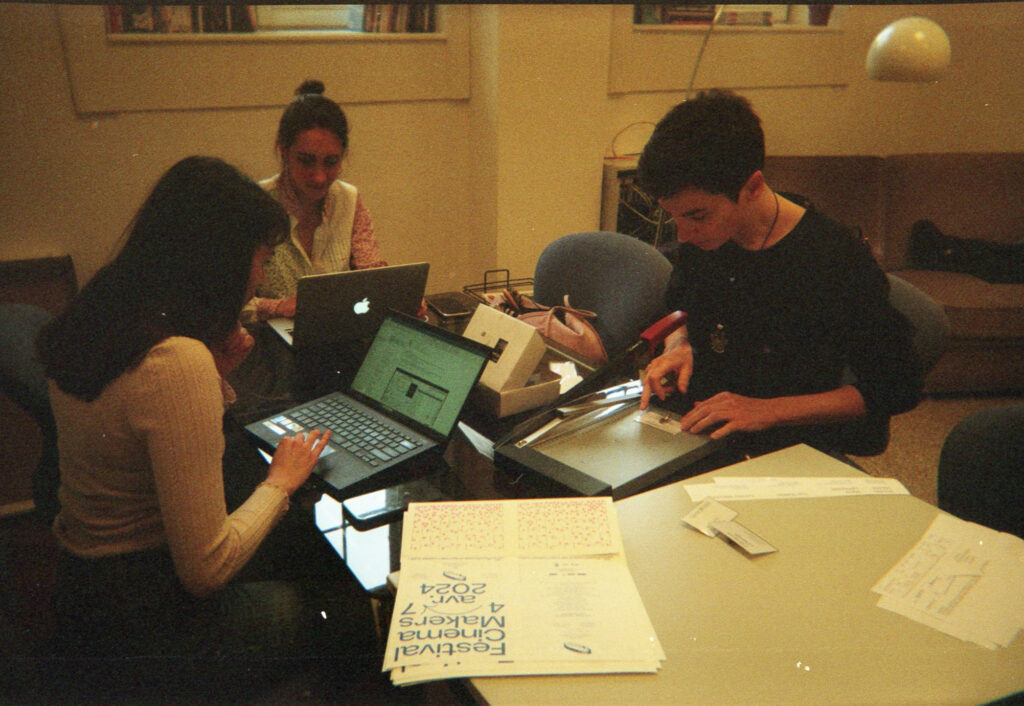

Film practitioners gather at Cinema Makers 2024 (Credit: Agnes Salson)

Film practitioners gather at Cinema Makers 2024 (Credit: Agnes Salson)

Since the 2016 Brexit referendum, for many UK film practitioners like myself opportunities to access inspiring ideas from Europe have dwindled. The cheerful notes of the Europa Cinemas ident are no longer heard in our cinema halls. So, it felt both exciting and illicit to take a beautiful, subsidized train ride between countries and spend four days in closed door meetings and public screenings with sixteen exhibitors who are seeking to create innovative spaces across Europe at the Strasbourg Cinema Makers Conference in March 2024.

Led by representatives from three compelling spaces – La Forêt Électrique in Toulouse, Café des Images in Caen la Mer and our hosts for the conference Strasbourg’s Le Cosmos – we spent four days pondering what a modern cinema could be. There was a pleasing eclecticism among the delegates, and no sense of hierarchy or superiority, as we each reflected on the challenges and benefits of our individual approaches. At Kino Rotterdam that approach meant six screens of rep programming, smashed burgers and good times, while if we move over to Croatia there’s Dokukino, exclusively showing documentaries to Zagreb audiences. The radically open Cinema La Clef Revival, a collectively occupied cinema in Paris, are on the verge of buying back their space following years of free screenings from their squatted home, while Cinesud in Herleen in the Netherlands, more or less offers a full scale production studio alongside its work as a cinema. What was common among the delegates was a healthy desire to share, tempered by a caution that these approaches emerge from a specific social scene, funding environment and team members; ‘translation’ was needed, not the instant gratification of extraction and implementation.

Infrequently does the future lie in ‘innovation’ in exhibition. The trends that held the greatest sway among the Cinema Makers participants felt very distant from start-up culture and far closer to organic social movements. As a result, they spoke to ideas that have circulated far longer than our current moment, even while making use of the ease of access offered by the digital. The following are the threads that felt strongest amongst the group. Few will be alien as concepts, but the extent, the foundational way they have been baked in and maintained to these spaces, is unique and gave me much pause for thought as I try to conceptualize opening my own cinema.

A group meal at Cinema Makers 2024

A group meal at Cinema Makers 2024

Volunteers and community

Amongst the group there was a genuinely searching, mission-driven vision of the potential of cinema, and community volunteering was a major driver of this energy. Volunteers not only prevent a cinema being carved in the image of a select few paid staff, they also require constant renewal. What are we doing, who are we doing it for, how do we do it? These are all questions that have to be asked more regularly with a flow of new people, with different experiences, potentially better ideas about how things can be done, and less anxiety about their livelihoods if they go against the building’s orthodoxy.

Very regularly when I consult with venues, my expertise is partly about being able to see the space with fresh eyes.Volunteers – if they are properly enfranchised to drive the venue, if they are not simply taking the place of paid labor – perform this same function.

In Barcelona, the Zumzeig Co-operative use the space of the building to advertise its openness. Taking the work of programming and other core functions out of a back office and into the public café, including staff meetings, makes it clear that anyone who comes to the cinema could also participate in its running.

Given that volunteering can reflect existing inequalities in society, how do we ensure that essential but unglamorous work is delivered by more people than those who are usually required to take on the ‘second shift’? Newcastle’s entirely volunteer-run Star & Shadow Cinema spoke about their Friday cleaning brunch club. Volunteers come together, do the tasks, and then share in food. Mixing pleasure with business means that more people want to come along, making the task lighter for all.

Many cinemas – especially those newly facing censorship like those in Germany – spoke of the value of simply being in space together, with any space for face-to-face discussion with those outside of your immediate social group (or social media bubble) helping to reduce community tension. Cinemas also could become platforms for other social movements. Through a circuitous route involving the screening of the utopian farming doc No Man is an Island, Cafés Des Images in Hérouville-Saint-Clair has become the local distribution point for Sicilian farmers who want to sidestep more exploitative routes to market. This gives people who would never otherwise step in the cinema a reason to build positive interactions with the venue.

A Cinema Makers session (Credit: Agnes Salson)

A Cinema Makers session (Credit: Agnes Salson)

Reshaping space

Thinking about space also occupied much of the discussion, especially as it relates to ownership and function. On one level, do you own the space, is it within municipal hands, or private ownership? Invisible to the average cinema-goer, ownership plays a foundational role in setting the direction of the building. If you don’t own the space, you are at greater risk of forces beyond your control: landlordism, gentrification, local (and national) government policy. Many spaces, having opened with traditional rental, used their central place in the community to move towards community buy out. Nova in Brussels, having bought their space – formerly overflow storage for a bank – now have a much more robust future. Cinema La Clef Revival, through the radical resistance of squatting, have drawn in people from their community and beyond, in tribute to the lasting value a cinema space has to their community. Other spaces – including our hosts Le Cosmos – have been granted the right by the municipality, sheltering them from ongoing market rate rents that can escalate the already considerable costs of opening a venue.

The other level where ‘cinema’ was being questioned is what activities are delivered within the building. While some looked enviously at stunning heritage spaces like Cinema Arta in Cluj, Romania, others attested to the inflexibility that comes from having a space that must remain as it was forged. Other spaces that have shaped themselves in the last few years spoke with mixed feelings about projection quality, but with great passion about the flexibility that had been baked in from inception. Podcasts, club nights, community meetings, crafting: at venues like Toulouse’s La Forêt Électrique, the cinema is a ‘third space’ that can encompass some of the functions of a town or church hall. While this moves the cinema away from its absolute purity of function and experience, it also makes it more robust and resilient, able to respond to different communities’ needs and interests, future-proofing it. Finally, some spaces – like Košice, Slovakia’s Kino Usmev – balanced the two, nobly taking a 1922 cinema and transforming it into a platform that is open to all, from Ukrainian refugees to blind audiences.

Make the film, show the film

The performance of cinema can play out like a magic trick. Filmmaking itself is a sealed box and the audience has no means to pry it open. Yet many of the spaces in the forum seek to make that process transparent. At the simplest level, cinemas are hotspots for active filmmakers and potential filmmakers, so simply giving them designated space and a time to gather and collaborate is a significant contribution to regional development. Other spaces offered full residencies for outside artists or for emerging talents.

One other exciting potential area of development – in direct contrast to a globalized film culture intended for all four quadrants and without any potentially alienating cultural specificity – was for cinemas to lead to a genuinely local filmmaking scene to develop. Almost every cinema has the success story of the film shot locally that was an enduring success, but what if cinemas reverse engineered this process, intentionally seeking to make films that respond to local concerns, local history and local landscapes? Perhaps these films might be parochial and never travel further, or perhaps by being extremely culturally specific, we can find the universal? Cinemas could be making their own Bait – a film borne out of hyper specific production methods and Cornish identity, but which became a surprise national and international hit. At the same time, the inverse is also possible, as with Berlin’s SİNEMA TRANSTOPIA, which points to an interconnectivity between aspects of many groups across nations. La Forêt Électrique’s current programme is an ode to regionalism, including highlighting their own Occitanian cinema.

With cinemas offering more space to filmmaking, they also present a chance for a film to meet its audience as it develops, with work-in-progress screenings and residencies giving a routes for directors to learn from and respond to the environment, as can be seen at Le Polygone Étoilé in Marseille and Cinesud in Holland. Filmmaking can be a frustratingly slow-moving format, but what if cinemas provided a platform for rapid creation and rapid exhibition to audiences? Whether these more informal versions of filmmaking provided a ‘wireframe’ version to be developed fully, or were complete in themselves, it allows cinemas to be active participants, rather than passive receivers, of the work they show on screen.

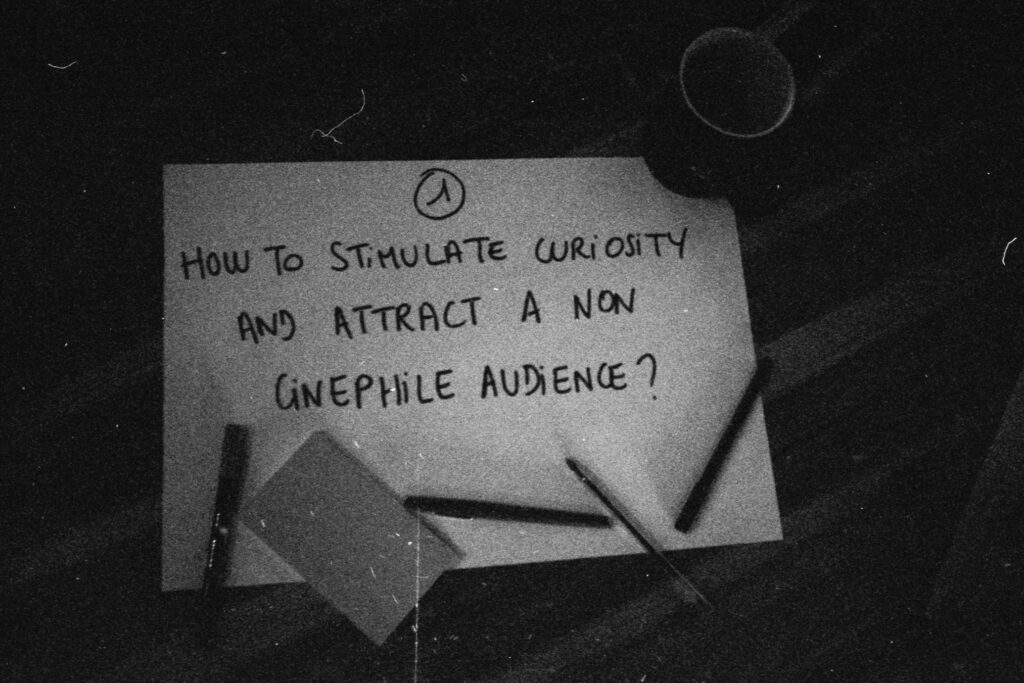

A Cinema Makers provocation (Credit Agnes Salson)

A Cinema Makers provocation (Credit Agnes Salson)

Experimenting with programme

Across the international array of participants, many shared the observation that there is increasing convergence of programming between multiplexes and arthouses, something I myself have also witnessed in the UK. Some cinemas spoke of a local pact of non-competition on certain titles, in order to encourage programme specialization, cross-promotion and diversity of screenings locally. Other cinemas found a lack of competition proving a problem. In Romania, there are only eight arthouses across nineteen million people, which has a network effect on distribution and mainstreaming of arthouse moviegoing.

Some cinemas were clear they would likely never move to a full time programme to take in the newest releases, either because other local arthouses covered this terrain, or because distributors’ show demands work against the flexibility they prize. Breaking away from this model means more space for personalized programming beyond the release calendar, often sourced by committees and working groups rather than the sacrosanct single programmer, high priest(ess) of cinema, releasing the gospel to the masses. Relying less on wide releases is undoubtedly more challenging. Rather than waiting for another Anatomy of a Fall to fall in our laps, we must generate interest ourselves in work that may only be known to the ardent cinephile. Take a look at the beautiful trailers from Kino Rotterdam that dispel any feelings of obscurity and hone in on universal appeal or the eye-catching Risograph printing of Le Cosmos, which draws in people who value aesthetics, not just as it’s expressed through film. Building a film culture of earned trust from audiences, independent from trends or cycles, hard though it may be, is in the long-term far more resilient.

Duncan Carson is a cinema worker and consultant who works with cinemas to help them find their possible audiences. He works at the UK’s Independent Cinema Office, leading on their conferences, distribution and partnerships. He is also a freelance cinema consultant and is aiming to bring a new cinema to Waltham Forest in London.